4. Package structure and state¶

The previous chapter provided a high-level demonstration of how to develop a Python package from scratch with the help of poetry. Later chapters will expand upon this demonstration and explore each of the key packaging steps in more detail, but before that, this chapter will describe in more detail what packaging means in Python and what packages actually are. Often, developers don’t think about packaging until their code is written - but we’ll learn that thinking about packaging before even writing any code is very useful! This chapter is a somewhat Pythonified version of the Package Structure and State chapter of the R Packages book written by Jenny Bryan and also draws on information from the Python Packaging Authority.

4.1. Package states¶

By “package” here we mean the code that you wish to bundle up and distribute. In Python, your package can be in several different states depending on its complexity, target audience, and stage of development. The ones we’ll talk about here are:

Modules

Packages

Source distributions

Built distributions

Binary distributions

Installed packages

Imported packages

Python applications

You’ve already seen some of the commands that put packages into these various states. For example, poetry build at the command line or import in a Python session. In the following sections, we’ll be giving those operations some context.

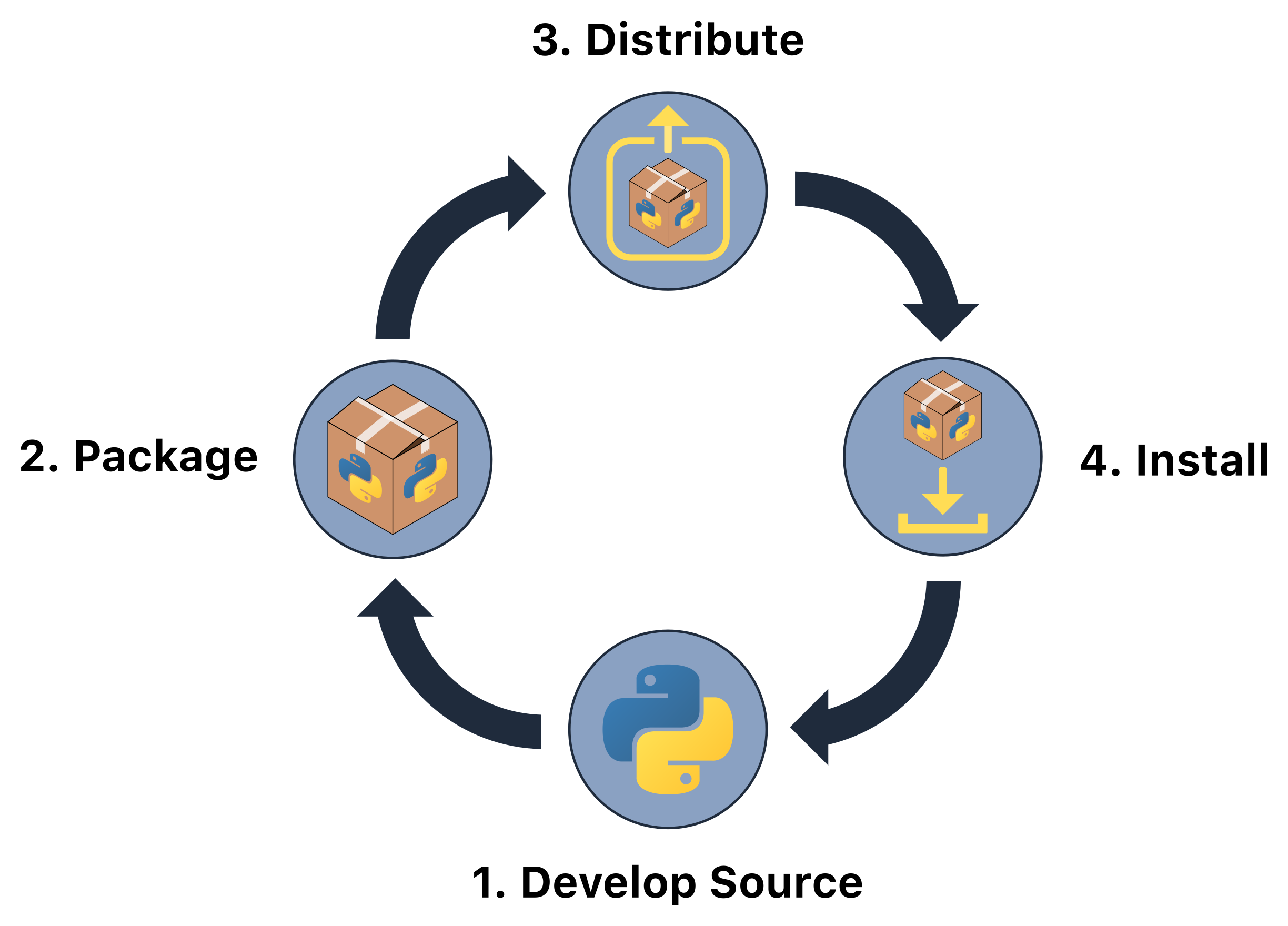

Fig. 4.1 The Python packaging workflow.¶

4.2. Modules¶

A module is any Python .py file. A module may consist of Python functions, classes, variables, and/or runnable code. A module that relies only on the standard Python library can easily be distributed and used by others (on the appropriate version of Python). In this way, a module can be thought of as a very simple package. For example, consider a module simple_math.py that contains the functions list_range and odd_even:

If the module simple_math.py is in your working directory then you can import the module using:

import simple_math # imports the entire module. Functions can then be accessed via dot notation, e.g., simple_math.list_range()

from simple_math import list_range # import only list_range function

from simple_math import odd_even # import only odd_even function

from simple_math import * # import all functions

Because modules are single files they can easily be shared to others by e.g., email, GitHub, Slack, etc. Another user would simply place the module in their working directory to use it. However, this method of distribution does not scale well in cases of multiple files, if your code depends on other libraries/packages, or needs a specific version of Python.

4.3. Python packages¶

Projects consisting of multiple Python .py files (i.e., modules) are, by their nature, harder to distribute. If your project consists of multiple files, it is typical to organise it into a directory structure. Any directory containing Python files can comprise a Python “package”.

While we’ve been using the term “package” fairly generically so far, it does have a specific meaning in Python and it’s important to make clear the distinction between “modules” and “packages”. As described in the previous section, any Python .py file is a module. In contrast, a package is a directory containing module(s) and/or additional package(s) (sometimes called “nested packages” or “subpackages”) along with an __init__.py file. An __init__.py file is required to make Python treat a directory as a package (as opposed to it simply being a plain-old directory of Python files); in the simplest case __init__.py is an empty file, but it can also execute initialization code for the package upon import (read more here). Packages allow us to structure and organise our Python code and intuitively access it using “dotted module names”. Consider having the following two packages in your working directory:

A package containing modules:

A package containing nested packages:

Modules can be accessed using dot notation. For example:

It would be possible to share a package by transferring all the files that comprise the package (keeping the directory structure intact) to another user, who could then use the package if it were placed in their working directory. However, just like single modules, this method of distribution does not scale well, makes it difficult to support or update your code, and won’t work if your code depends on additional libraries, or needs a specific version of Python. We need a more efficient and reliable way to package and distribute our code which leads us to “source distribution packages” and “built distribution packages” which are described below.

4.4. Source distribution packages¶

A “distribution package” (often referred to simply as a “distribution”) is a single archive of the Python packages, modules and other files that make up your project. Having a single archive makes it easier to distribute your code to the world. The fundamental distribution format is called a “source distribution” (sdist). An sdist is a compressed archive (e.g., .tar.gz or .zip) of your package. Essentially, an sdist provides all of the metadata and source files needed for building and installing your package. You can read more about source distributions here. The standard tool in Python for creating sdists (and binary distributions, which we’ll explore in the next section) is setuptools.

Note

As we saw in How to package a Python, we prefer to use poetry to create distribution packages of our Python code, as a simpler and more intuitive alternative to setuptools. We’ll discuss Poetry a little later.

As a very simple example, consider the following directory which now contains a setup.py file.

The setup.py file is a standard file that contains metadata about your project and helps setuptools build your sdist - in the very simplest case, it may look like this:

We won’t talk about setup.py too much more as we will advocate for using poetry for building and distributing your packages (we’ll get to that a little latter), but if you see a setup.py file somewhere in your packaging jounrey at least you now know what it’s for! If you want to learn more about creating a setup.py file, it is described in detail here. If you do decide to use setuptools for building your package and you have your setup.py file all set up, your sdist can be built by changing to the root directory of your package and running the following command:

This will create an archive file (.tar.gz by default) of your project which is your sdist. If your code is pure Python then an sdist is a perfectly acceptable way to distribute your code, and a user could install it using:

You could also share your sdist to PyPI from which a user could install it using pip install. It’s important to note that installing a package actually adds the package to your default installation directory (more on that later in the chapter) such that it is accessible outside of your working directory - this is a key difference to simply sharing code as a module or package as we explored in the last two sections. We recommend consulting the The Hitchhiker’s Guide to Packaging and the Python docs for more information on creating and distributing source distributions. Some notable examples of Python sdists include: Django, hyperlink, and requests.

4.5. Built distribution packages¶

Source distributions are “unbuilt” and require a build step before they can be installed. This nuance is most relevant in cases where your code relies on non-Python code/libraries that require building (aka “compilation”) before they can be used (more on that in the next section). However, even if your package is written in pure Python, a build step is still required to build out the installation metadata. As a result, built distributions are the preferred format for distributing your Python packages. They are packages that have been pre-built and do not require a build step before installation - they only need to be moved to the correct location on your system (as we’ll explore more later in the chapter). Like a source distribution, a built distribution is a single artefact, and the main built distribution format used by Python is called a wheel.

Python’s installer pip always prefers installing built distributions (wheels) over source distributions (sdists) because installation is faster. Building wheels is similar to building source distributions with setuptools as described in the previous section. We won’t go into details here because for most users we recommend the use of poetry (described later in this chapter) which handles this build process for you in a simple and intuitive way. However, if you’re interested in learning more about using setuptools to build a wheel of your project we recommend taking a look at the Python Packaging User Guide tutorial.

If your code relies on any non-Python code/libraries, you’ll need to use a specific kind of built distribution known as a binary distribution to bundle up your package, which is described in the next section.

4.6. Binary distribution packages¶

One of the most powerful features of Python is its ability to interoperate with libraries written in other languages, for example, C. Developers sometimes choose to take advantage of this interoperability and include code from other languages in their package to make their code faster, access libraries written in other languages, and generally improve the functionality of their code. While Python is typically referred to as an interpreted language (i.e., your Python code is translated to machine code as it is executed), languages such as C require compilation before they can be used (i.e., your code must be translated into “machine code” before it can be executed). Most end-users will probably not have the tools, experience, or time to build packages containing code written in other languages (typically called “extensions”), so in these cases binary distributions are how you make life as easy as possible for installers of your code. Binary distribution packages are simply packages that contains pre-compiled extensions - as an analogy, you can think of your source code as a cake recipe, while a binary distribution is the fully cooked cake.

For example, much of the commonly used Python library NumPy is implemented as C extensions. The existence of pre-built wheels in Python means that a user can, for example, simply run pip install numpy to install NumPy from PyPi, as opposed to having to build it from source with the help of a C compiler, amongst other requirements. If you’re feeling particularly masochistic you can actually try to build NumPy from source following these instructions from the NumPy docs.

Recall that binary distributions contain compiled code (code that has been translated from human-readable form to machine code), but different platforms (i.e., Windows, Mac, Linux) read machine code differently. As a result, binary distributions are platform specific. For this reason, binary distributions are usually provided with their corresponding source distributions; if you don’t upload binary wheels of your code for every platform, end-users will still be able to build it from source. Take a look at the downloadable file list of NumPy on PyPi - you’ll see wheels for most common platforms, as well as the source distribution at the bottom of the list. wheels actually come in three flavours (which you can read more about here):

Universal wheels: pure Python and support Python 2 and 3. Can be installed anywhere using

pip.Pure Python wheels: pure Python but don’t support both Python 2 and 3

Platform wheels: binary package distributions specific to certain platforms as a result of containing compiled extensions.

You can tell a lot about a wheel from the name itself which follows a strict naming convention: {distribution}-{version}(-{build tag})?-{python tag}-{abi tag}-{platform tag}.whl. For example, the NumPy wheel numpy-1.18.1-cp37-cp37m-macosx_10_9_x86_64.whl tells us that:

The distribution is

NumPy v1.18.1;It is made for Python 3.7;

It is specific to the

macosx_10_9_x86_64platform (i.e, this is a “platform wheel” because it is platform-specific).

Most readers will never deal with building extensions in other languages for their Python package, so this section is intended to be read as general information on Python’s packaging ecosystem and the wheel format. However, if you are interested in building binary extensions for your package, the Python Packaging Authority guide is a good place to start.

4.7. Poetry and pyproject.toml¶

The previous sections gave a high level overview of Python’s standard packaging options and tools. However, in How to package a Python we used poetry to create a toy Python package - so where does this tool fit into the Python packaging landscape? Well, in the previous sections, we really only touched the tip of the iceberg of Python packaging. When creating a package there’s a lot of customisation to think about with your setup.py file, and a host of other files we didn’t even talk about (e.g., requirements.txt, setup.cfg, etc)! Needless to say, packaging in Python can be hard to understand, especially for beginners. These words echo the sentiments of poetry's creator Sébastien Eustace and the motivation for creating the tool:

“Packaging systems and dependency management in Python are rather convoluted and hard to understand for newcomers. Even for seasoned developers it might be cumbersome at times to create all files needed in a Python project: setup.py, requirements.txt, setup.cfg, MANIFEST.in, and the newly added Pipfile. So I wanted a tool that would limit everything to a single configuration file to do: dependency management, packaging and publishing.”

That “single configuration file” is pyproject.toml (you can read more about .toml files here). Essentially, poetry is based on all the concepts of sdists and wheels discussed previously - it just simplifies and streamlines the whole packaging process in an intuitive way. In fact, the poetry build command you used previously in Chapter 3: How to package a Python, actually creates the sdist and wheel distributions of your package for you. It really is simple to create and distribute Python packages with poetry - go back and check out How to package a Python for our recommended workflow, or check out the poetry docs.

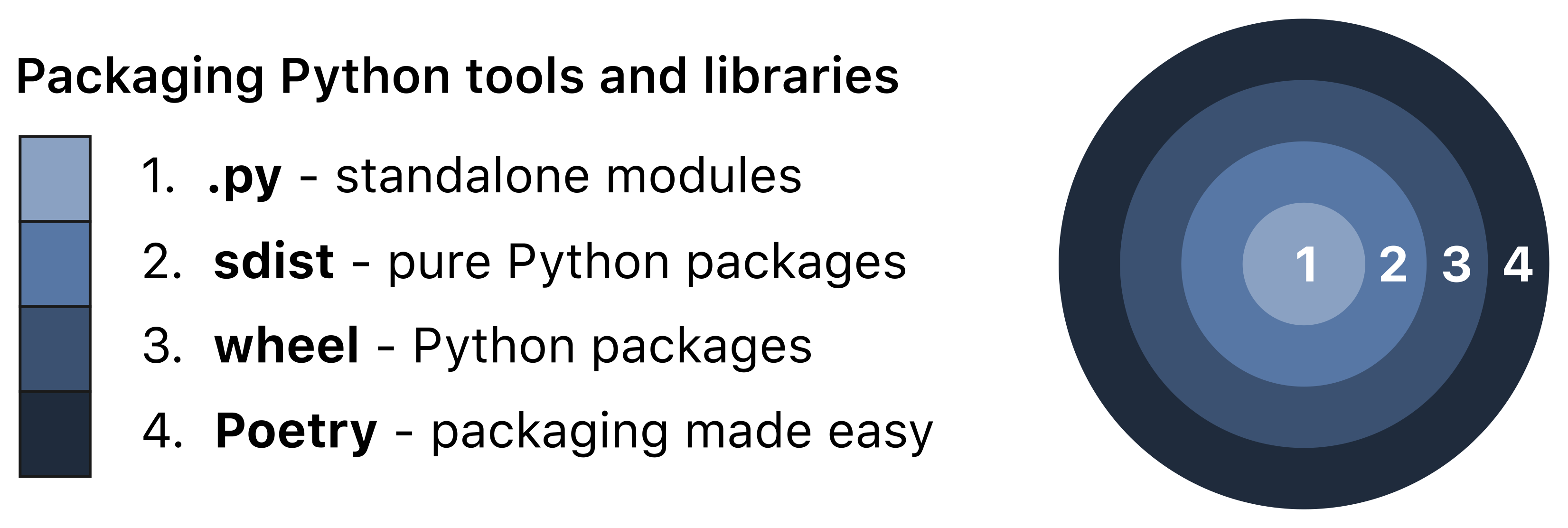

Fig. 4.2 Python packaging gamut. Modified after The Packaging Gradient by Mahmoud Hashemi.¶

4.8. Installed packages¶

An installed package is a distribution that’s been decompressed, built (in the case of an sdist) and then copied to your chosen installation directory. The default “chosen installation directory” varies by platform and by how you installed Python. For example, I installed Python using the miniconda distribution and my default directory for package installation is /Users/tbeuzen/miniconda3/lib/python3.7/site-packages.

“Installing” a package (e.g., by pip install XXX) is really a two-step process: 1) building the package, and 2) installing the package. Using wheels takes out the first step, meaning we only need to install. The install step is simple, all it really has to do is copy decompressed package files to the appropriate directory. In fact, we can manually install a package ourselves if we want to by manually decompressing a wheel and copying the files to their appropriate locations - there’s no real reason to do this because it’s far more effort than using a single one-liner at the CL, it does not resolve dependencies so could break your installation, and probably has other unwanted side-effects. However, it’s a nice way to learn about the package installation process, so if you’d like to give it a go, you can try the following steps (which are based on using the MacOS and conda package manager):

Create a new virtual environment to act as a safe, test playground. As a

condauser, the CL command for me to create and then activate a new empty virtual environment called “manualpkg” including Python 3.7 is:You can find a toy

wheelto download in the GitHub repository of this book here (although you can try this manual installation procedure with awheeldownloaded from any source, e.g., PyPI). Download thewheelinto thesite-packagesdirectory of themanualpkgenvironment, which for me was located at/opt/miniconda3/envs/manualpkg/lib/python3.7/site-packages;From the CL, change to that

site-packagesdirectory and unzip the wheel:You’ll now find two new unzipped directories

toy_pkgandtoy_pkg-0.0.1.dist-info;From the CL start a Python session by typing

pythonand try the following:You can remove the

condavirtual environment if you wish with the following:

4.9. Imported packages¶

We now arrive at our last package state, the “imported package”. This state is associated with a command that is familiar to everyone that uses Python:

You can read about the import system in detail in the Python documentation. Briefly, the import statement comprises two operations:

it searches for the named module; and,

then binds the results of that search to a name in the local namespace.

Note that for efficiency, each module is only imported once per interpreter session. If you modify your module, you can’t just re-run your import statement (as that name in the namespace is already populated and won’t be re-loaded). Instead, you have to restart your interpreter or force the import using importlib.reload(), but this is inefficient when working with multiple modules.

4.10. Packaging Python applications¶

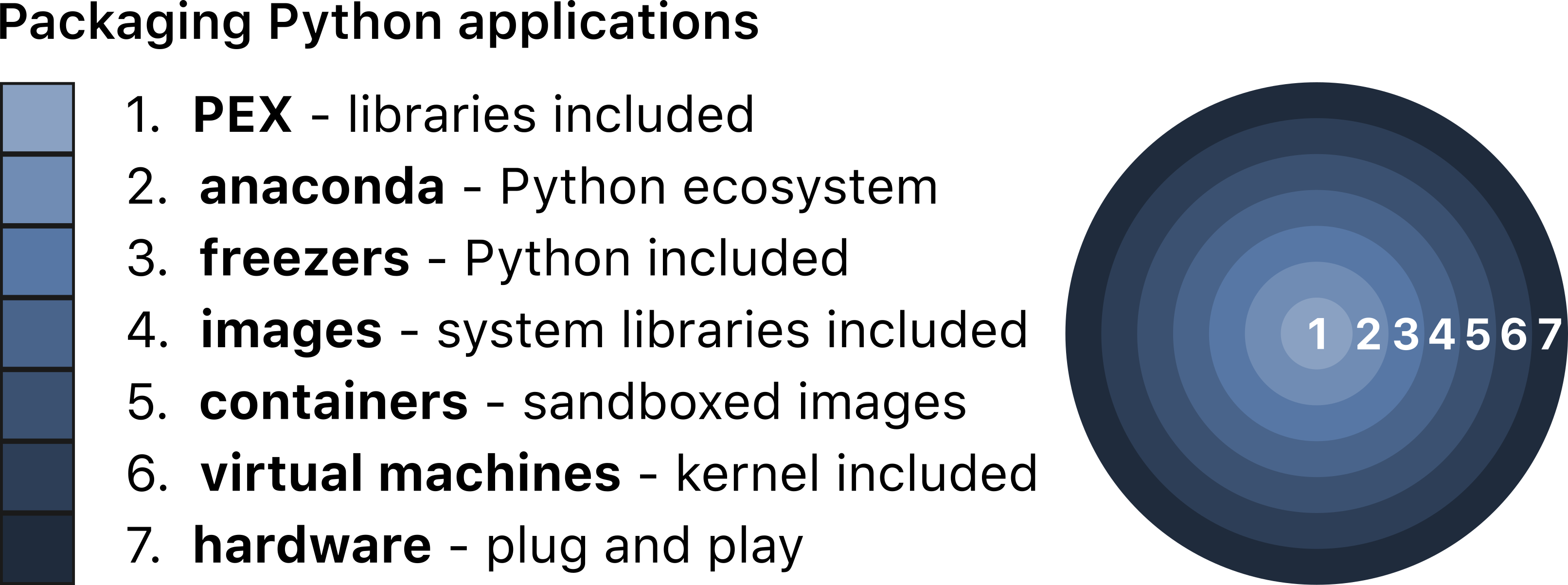

In this chapter we’ve only talked about packaging and distributing reusable Python code, a process which is really aimed at developers and audiences familiar with Python. While it’s outside the scope of this book, it’s also possible to package and distribute entire Python applications, that is, software that is meant to be used rather than developed on. Some good examples of Python-based applications are Sublime Text, EVE online, and Reddit. There are a lot of options available for packaging and distributing Python applications and we recommend watching the excellent talk by Mahmoud Hashemi “The Packaging Gradient” to learn more. To give you an idea of the available options, the figure below shows a summary of the different options discussed by Mahmoud for packaging Python applications.

Fig. 4.3 Python application packaging gamut. Modified after The Packaging Gradient by Mahmoud Hashemi.¶